I got a copy of the Science article by Van Mantgem et. al. on tree mortality referred to in my previous post here. I have not done a comprehensive review, but I have now read it and its supplements and have a few immediate reactions.

This article struck me as an absolutely classic academic study, for the following reason: The study can be broken up into two parts – measurement of a natural phenomenon and possible explanations for the measurements. The meat of the effort and real work is in the first part, the measurement of tree mortality, with very weak work on the second part, on the links to global warming. Many academic studies are guilty of this to some extent. I once had a professor tell me every study was a year of intensive data gathering and analysis followed by 2 hours of a group of grad students trying to brainstorm causes and implications, the more exciting the better. Unfortunately, the press releases and media attention in climate tend to focus on this hypothesizing as if it had as much credibility as the actual data analysis. Let me be specific.

The first part of the study, the measurement of tree die-off rates, appears to be where the bulk of the work is, and their findings seem fairly reasonable — that tree die-off rates seem to have gone up over the last several decades in the western US, and that this die-off seems to be consistent across geography, tree size, and tree type. My only complaint is that their data shows a pretty clear relationship between study plot size and measured mortality. Most of the measured tree mortality is in plots 1 hectare or less (about 2.5 acres, or the size of a large suburban home lot). There is not nearly as much mortality in the larger study plots — I would have liked to see the authors address this issue as a possible methodological problem.

Anyway, the finding of large and spatially diverse increases in mortality of trees is an important finding, and one for which the authors should feel proud to identify. The second part of the study, the hypothesized causes of this mortality, is far far weaker than the first, though this is not atypical of academic studies. Remember, in the press summaries, the authors claimed that global warming had to be the cause because they had eliminated everything else it could possibly be. So here is what their Science article mentions that they considered and rejected as possible causes:

- Changes in forest density and fire exclusion policies

- Old trees falling and crushing new trees

- Ozone levels (they claim they look at “pollution” but ozone is the only chemical discussed)

- Activity of fungal pathogen, Cronartium ribicola, in certain pines

- Forest fragmentation

Wow, well that certainly seems comprehensive. Can’t think of a single other thing that could be causing it. By the way, the last one is interesting to me, because I suggested forest fragmentation and micro-climate issues in my first post. So, just to give you an idea of the kind of scholarship that passes peer review, let’s see how they tested for forest fragmentation: they compared mortality of trees inside national parks vs. mortality of trees outside of national parks. The logic is that National Park trees would see less fragmentation over time since they are protected from logging, but that of course is a supposition.

This is really weak. I guess it’s not a bad test if you had to come up with such a test in an afternoon without the time to do any extra work, but it is a very course macro test of a very micro problem. For example, the top of Kilimanjaro is protected as a National Park, but evidence is pretty strong that snow on the mountain is being reduced by land-use-related changes in precipitation and local climate due to logging outside the national park.

A lot of folks in the comments of the last post mentioned, reasonably, the massive infestations of western pine bark beetles. The only mention of the bark beetle infestations was, interestingly, in their last paragraph, where they said:

First, increasing mortality rates could presage substantial changes in forest structure, composition, and function (7, 25), and in some cases could be symptomatic of forests that are stressed and vulnerable to abrupt dieback (5). Indeed, since their most recent censuses, several of our plots in the interior region experienced greatly accelerated mortality due to bark beetle outbreaks, and in some cases nearly complete mortality of large trees

I guess that is a handy way to deal with an exogenous factor you don’t want to admit drove some of your observations – just reverse the causality. So now mortality is not caused in part by beetles, beetles are caused by mortality!

By the way, before I head into temperature, I had a question for those of you who may know trees better than I. Do trees have demographics and generations, like human populations? For example, we expect a rise in mortality among humans over the next 30 years because there was a spike in birth rates 50 years ago. Do forests have similar effects? It struck me that humans cleared a lot of western forests from 1860-1920, and since then the total forested area in the US has expanded. Is there some sort of baby boomer generation of trees born around 1900 that are now dying off?

Anyway, on to temperature. Here is the key statement from the Science article:

We suggest that regional warming may be the dominant contributor to the increases in tree mortality rates. From the 1970s to 2006 (the period including the bulk of our data; table S1), the mean annual temperature of the western United States increased at a rate of 0.3° to 0.4°C decade−1, even approaching 0.5°C decade−1 at the higher elevations typically occupied by forests (18). This regional warming has contributed to widespread hydrologic changes, such as declining fraction of precipitation falling as snow (19), declining snowpack water content (20), earlier spring snowmelt and runoff (21), and a consequent lengthening of the summer drought (22). Specific to our study sites, mean annual precipitation showed no directional trend over the study period (P = 0.62, LMM), whereas both mean annual temperature and climatic water deficit (annual evaporative demand that exceeds available water) increased significantly (P < 0.0001, LMM) (10). Furthermore, temperature and water deficit were positively correlated with tree mortality rates (P ≤ 0.0066, GNMM; table S4).

The footnotes reference that the temperature and water correlations are in the supplementary online material, but I have access to that material and there is nothing there. I may be unfair here, but it really looks to me like some guys did some nice work on tree mortality, couldn’t get it published, and then tacked on some stuff about global warming to increase the interest in it. Note that Science recognizes what the study is about, when it titles the article “Widespread Increase of Tree Mortality Rates in the Western United States,” without mention of global warming. But when it moves to the MSM, it is about global warming, despite the fact that none of the warming and drought data and regressions are considered important enough or persuasive enough to make the article or even the supplementary material.

OK, if this paragraph is all we have, what can we learn from it? Well, the real eye-catcher for me is this:

From the 1970s to 2006…the mean annual temperature of the western United States increased at a rate of 0.3° to 0.4°C decade−1, even approaching 0.5°C decade−1 at the higher elevations typically occupied by forests

They are saying that for the period 1971-2006 the temperature of the Western US increased 1.1°C to 1.4°C, or 2-2.5°F. And it increased as much as 6.3°F in the higher elevations. This seems really high to me, so I wondered at the source. Apparently, it is coming from something called the PRISM data base. These guys seem to have some sort of spacial extrapolation program that takes discreet station data and infills data for the area between the stations, mainly using a linear regression of temperature vs. altitude. I have zero idea if their methodology makes any sense, but knowing the quality of some of the station data they are using, it may be GIGO. (By the way, someone at Oregon State, who apparently runs this site, needs to hire a better business manager. Their web site repors that in an academic environment awash with money for climate research, their climate data base work has been suspended for lack of funding).

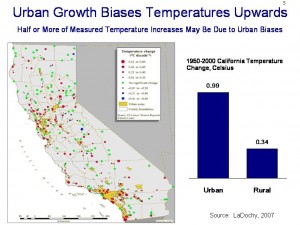

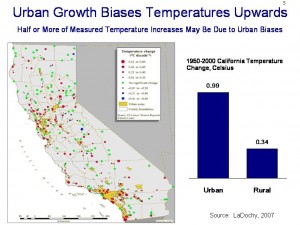

As a back check on this number, LaDochy in 2007 looked at California temporal and spatial temperature trends in some depth. He found that when one pulls out the urban stations, California rural areas experienced a 0.034C per decade temperature increase from 1950-2000, an order of magnitude lower than the numbers this study is using (click to expand slide below):

Satellite data from UAH, which does not have the same urban bias problems, shows near-surface temperatures rising 0.1-0.3C per decade from 1978-2006 in the study areas, higher than the LaDochy numbers but still well below the study numbers.

This is a real problem with the study. If you really want to measure the impact of temperature and participation on a 2.5 acre lot, you have to actually measure the temperature and precipitation, and even better things like the soil moisture content, somewhere near the 2.5 acre lot, and not look at western averages or computer interpolated values.

The study authors conclude:

Warming could contribute to increasing mortality rates by (i) increasing water deficits and thus drought stress on trees, with possible direct and indirect contributions to tree mortality (13, 23); (ii) enhancing the growth and reproduction of insects and pathogens that attack trees (6); or (iii) both. A contribution from warming is consistent with both the apparent role of warming in episodes of recent forest dieback in western North America (5, 6) and the positive correlation between short-term fluctuations in background mortality rates and climatic water deficits observed in California and Colorado (13, 24).

I guess I won’t argue with the word “consistent,” and I suppose it is unfair to hammer these guys too hard for the way the MSM over-interprets the conclusions and latches on to the global warming hypothesis, but really, isn’t that why the warming material is included in the paper, to get attention for the authors? Because this paragraph would be a nice summary in a paper proposing a new study, and the hypothesis is a reasonable one to test, but it certainly isn’t proven by this study.

Postscript: From the map, some of the test plots are almost right on top of the California bristlecone pines used for climate reconstruction. Remember, Mann and company begin with the assumption that tree growth is positively correlated with temperature. This article argues that warming is stunting tree growth and causing trees to die. While these are not impossible to reconcile (though its hard considering the authors of this study said their findings were consistent across tree age, size, and variety) I would love to see how the RealClimate folks do so.

Update: Note that I still have not read the complete study itself, so I am sure there are climate regressions and such that did not make the publication or the online exhibits in Science. So this quick reading may still be missing something.

Update #2: The best reconciliation I have received on this study vs. dendro-climatology work is the following, and is suggested on this page. Certain trees seem to be growth-limited by temperatures, and certain trees are growth limited by water (I presume there are other modes as well). Trees that are temperature-limited will have their growth gated by temperature. Trees that are water-limited will have growth controlled primarily by precipitation levels. Grassino-Mayer states:

…sites useful to dendrochronology can be identified and selected based on criteria that will produce tree-ring series sensitive to the environmental variable being examined. For example, trees that are especially responsive to drought conditions can usually be found where rainfall is limiting, such as rocky outcrops, or on ridgecrests of mountains. Therefore, a dendrochronologist interested in past drought conditions would purposely sample trees growing in locations known to be water-limited. Sampling trees growing in low-elevation, mesic (wet) sites would not produce tree-ring series especially sensitive to rainfall deficits. The dendrochronologist must select sites that will maximize the environmental signal being investigated. In the figure below, the tree on the left is growing in an environment that produced a complacent series of tree rings.

So I suppose that while most trees are suffering from higher temperatures via the moisture mechanism, so may be benefiting, and the key is to pick the right trees.

Of course, given that bristlecones were selected as much for the fact that they are old as the fact their growth is driven by one thing or another, the problem is how one knows a particular tree’s is temperature or moisture driven, and how one can have confidence that this “mode” has not changed for a thousand or more years.

Are bristlecones driven by temperature (as they are at fairly high altitude) or by precipitation (as they are in a very arid region of the southwest). One might expect that given divergence issues in the bristlecone proxies, the Mannian answer of “temperature” might be wrong. The NASA site offers this answer on the bristlecones:

Douglas’ [bristlecone] rings [from the White Mountains of CA, the same ones Mann uses] tell about rainfall in the southwestern United States, but trees also respond to changes in sunlight, temperature, and wind, as well as non-climate factors like the amount of nutrients in the soil and disease. By observing how these factors combine to affect tree rings in a region today, scientists can guess how they worked in the past. For example, rainfall in the southwestern United States is the factor that affects tree growth most, but in places where water is plentiful, like the Pacific Northwest, the key factor affecting tree ring growth may be temperature. Once scientists know how these factors affect tree ring formation, scientists can drill a small core from several trees in an area (a process that does not harm the tree) and determine what the climate was in previous years. The trees may also record things like forest fires by bearing a scar in a ring.