Years ago, when I was studying engineering in college, I had a professor who used to "joke" (remember, these are engineers, so the bar for the word "joke" is really low) that when he wanted to prove something, it was a real benefit to have only one data point. That way, he said, you could plot a trend in any direction with any slope you wanted through the point. Once you had two or three or more data points, your flexibility was ruined.

I am reminded of this in many global warming articles in the press today. Here is one that caught my eye today on Tom Nelson’s blog. There is nothing unusual about it, it just is the last one I saw:

Byers said he has decided to run because he wants to be able to look at his children in 20 or 30 years and be able to say that he took action to try to address important challenges facing humanity. He cited climate change as a “huge” concern, noting that this was driven home during a trip he took to the Arctic three weeks ago.

“The thing that was most striking was how the speed of climate change is accelerating—how it’s much worse than anyone really wants to believe,” Byers said. “To give you a sense of this, we flew over Cumberland Sound, which is a very large bay on the east coast of Baffin Island. This was three weeks ago; there was no ice.”

Do you see the single data point: Cumberland Sound three weeks ago had no ice. Incredibly, from this single data point, he not only comes up with a first derivative (the world is warming) but he actually gets the second derivative from this single data point (change is accelerating). Wow!

We see this in other forms all the time:

-

We had a lot of flooding in the Midwest this year

-

There were a lot of tornadoes this year

-

Hurricane Katrina was really bad

-

The Northwest Passage was navigable last year

-

An ice shelf collapsed in Antarctica

-

We set a record high today in such-and-such city

I often criticize such claims for their lack of any proof of causality (for example, linking this year’s floods and tornadoes to global warming when it is a cooler year than most of the last 20 seems a real stretch).

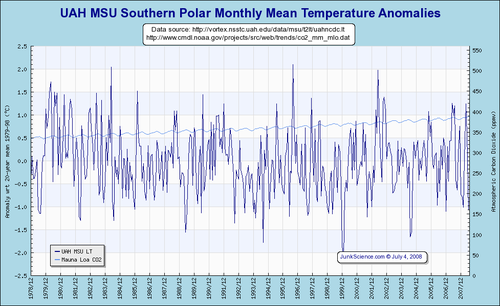

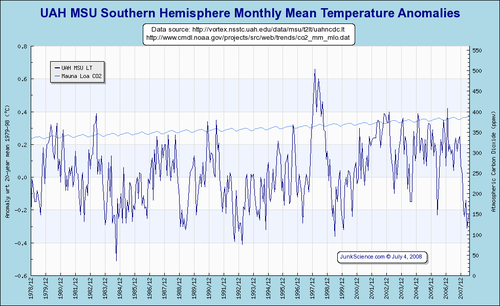

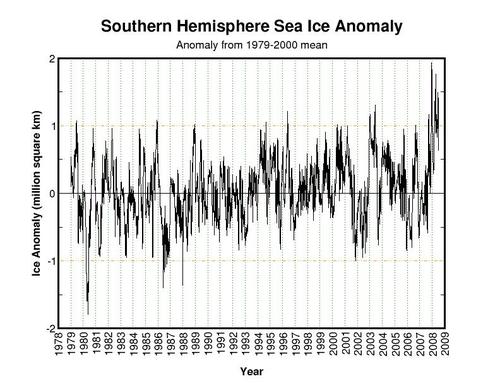

But all of these stories share another common problem – they typically are used by the writer to make a statement about the pace and direction of change (and even the acceleration of this change), something that is absolutely scientifically impossible to do from a single data point. As it turns out, we often have flooding in the Midwest. Neither tornadoes nor hurricanes have shown any increasing trend over the past decades. The Northwest Passage has been navigable a number of years in the last century. During the time of the ice shelf collapse panic, Antarctica was actually setting 30-year record highs for sea ice extent. And, by simple math, every city on average should set a new 100-year high temperature record every 100 days, and this is even before considering the urban heat island effect’s upward bias on city temperature measurement.

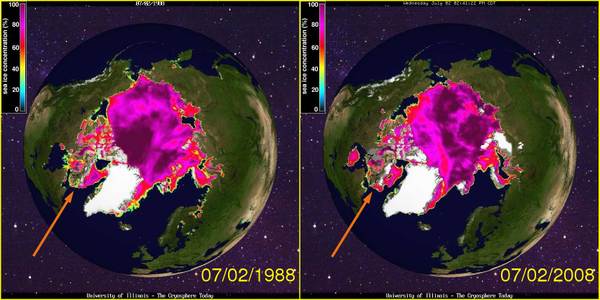

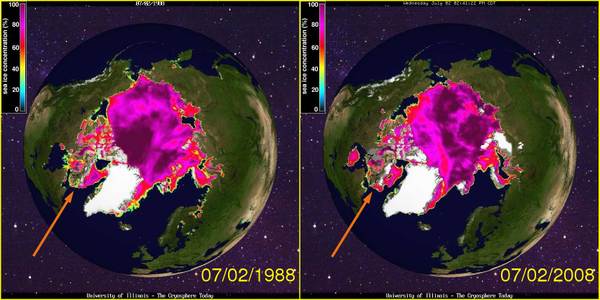

Postscript: Gee, I really hate to add a second data point to the discussion, but from Cyrosphere Today, here is a comparison of the Arctic sea ice extent today and exactly 20 years ago (click for a larger view)

The arrow points to Cumberland Sound. I will not dispute Mr. Byers personal observations, except to say that whatever condition it is in today, there seems to have been even less ice there 20 years ago.

To be fair, sea ice extent in the Arctic is down about a million square kilometers today vs. where it was decades ago (though I struggle to see it in these maps), while the Antarctic is up about a million, so the net world anomaly is about zero right now.